radicalism out of love for one's country

portrait of the mind of a popular Czech historian who smuggled radical imaginations from disinformation websites into the mainstream

Daniel Prokop explains how false analogies skew our comprehension of reality

instead of flat refusal of diversity, politicians could waive the tendency of multiculturalism to institutionalize ethnic differences and refuse the tendency of assimilationism to treat immigrants as aliens

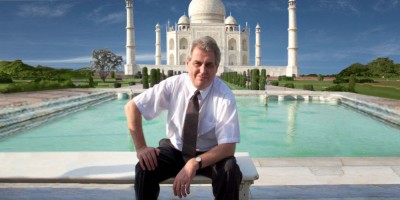

in a COMMENTARY, Jordanian Prince Hassan bin Talal reflects on the development of international standards of refugee protection in contrast with contemporary rise of nationalism