Migration

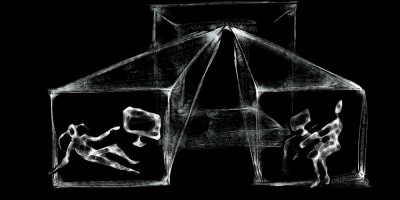

architecture of human solidarity

in a COMMENTARY, Jordanian Prince Hassan bin Talal reflects on the development of international standards of refugee protection in contrast with contemporary rise of nationalism

Dec 18th 2019

Hassan bin Talal

Articles by Datalyrics were published in